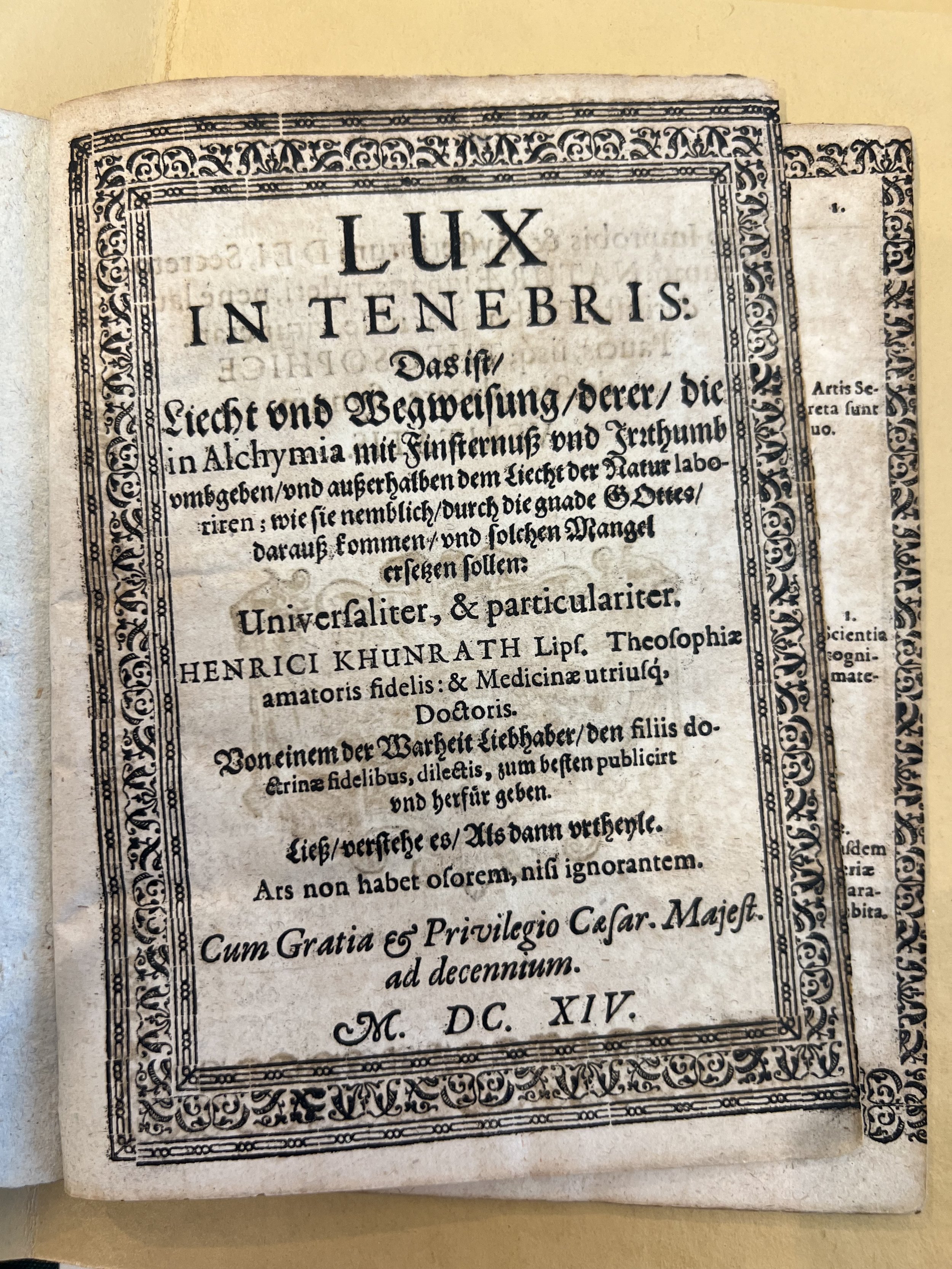

Lux In Tenebris

By Heinrich Khunrath

Also Known As:

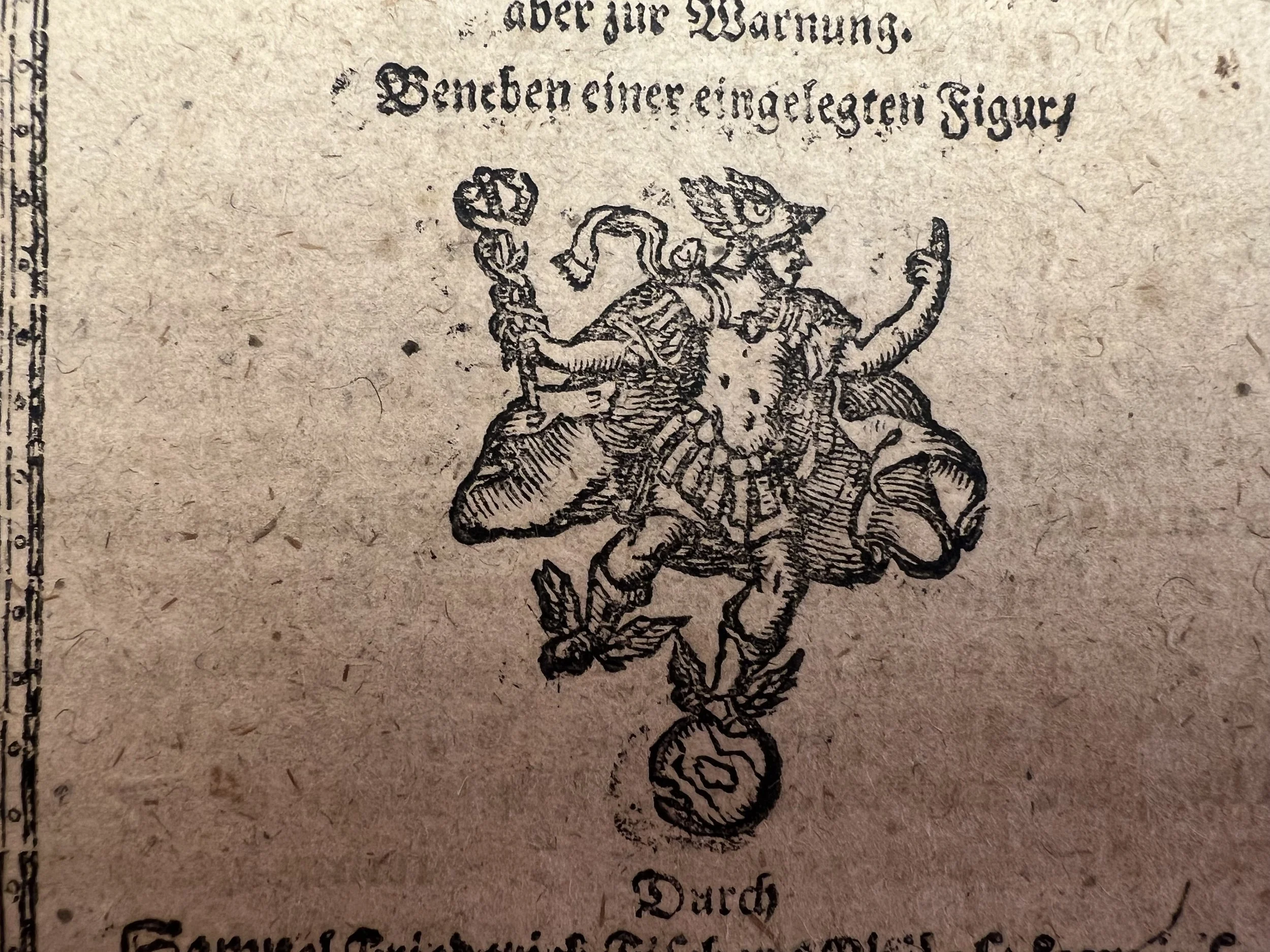

Lux in tenebris, das ist, Liecht vnd Wegweisung, derer, die in alchymia mit Finsternuss vnd Irrthumb vmbgeben, vnd ausserhalben dem Liecht der Natur laboriren : wie sie nemblich, durch die gnade Gottes, darauss kommen, vnd solchen Mangel ersetzen sollen : universaliter & particulariter

Description

Title

Lux in tenebris, das ist, Liecht vnd Wegweisung, derer, die in alchymia mit Finsternuss vnd Irrthumb vmbgeben, vnd ausserhalben dem Liecht der Natur laboriren : wie sie nemblich, durch die gnade Gottes, darauss kommen, vnd solchen Mangel ersetzen sollen : universaliter & particulariter

Creator

Khunrath, Heinrich, 1560-1605, author

Published / Created

MDCXIV [1614]

Publication Place

Germany?

Publisher

publisher not identified

Description

BEIN Rs5 K52 614: Number 1 of 2 titles bound together. Manuscript titles on cover.

Signatures: A-C⁴ D⁶(D6 [blank?] wanting).

Final page blank.

Extent

[2], 31, [1] pages ; 18 cm (4to)

Extent of Digitization

This object has been completely digitized.

Language

German

Collection Information

Repository

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Call Number

Subjects, Formats, And Genres

Genre

Resource Type

Subject (Topic)

Subjects

Access And Usage Rights

Access

Public

Lux Lucens in Tenebris opens with two paraphrased and fused passages from the book of Daniel and Psalms as a grateful prayer to God for allowing him insight into the workings of Nature. In his Vom Chaos, Khunrath identifies the light mentioned in Psalms 36.9 (369 = vortex mathematics) as the Light of Nature, which all true practitioners of Christian Kabbalah, divine magic and alchemy have sought both in the liber mundi and within themselves, lending them great power. This dual aspect of the Light of Nature is also found in Khunrath’s thought, as the Light of Nature is the source of the alchemist’s knowledge and power and found throughout Creation, from the angels, sunlight and empyrean waters to the creatures and metals of the earth – the everlasting spirit of God itself. The fountain of life mentioned in his prayer denotes the life-imparting distillation processes within the alchemist’s vessel, which itself is a microcosm of God’s Creation.

Khunrath continues in Lux Lucens in Tenebris with a customary condemnation of being in godless times, in which the true science of Nature granted by God to humankind has been lost and the wrath of God has been brought down upon society by those who care only for their own selfish goals. The same sentiments concerning the loss of the Prisca Sapientia are found also in the opening words of the Fama Fraternitatis (1614), although there the restoration of the “spotted and imperfect arts” is said to be well underway.

However, in Khunrath’s eyes, the ‘old philosophers and magi’ amongst the pre-Christian pagans held the wonders of God’s Creation in higher esteem than certain so-called Christians. Indeed, through their researches into the destruction and rebirth of metals they not only came to recognise the manner in which the human body may similarly be reborn, but also became aware of the existence of the Holy Trinity, the birth of the Saviour from a virgin, the transfiguration of the body of Christ, and his resurrection and return to his Father. In the late 5th century Theosophia, for example, followed certain of the Church fathers in claiming that the Sybilline oracular prophecies and the wisdom of ancient ‘theologians’ such as Orpheus demonstrated pagan foreknowledge of the coming of Christ, whilst Pierre Abélard controversially attributed knowledge of the Trinity to Plato. Although the passion of Christ had been employed since the Middle Ages to figuratively portray the alchemical work, Khunrath’s innovation here is his suggestion that such mysteries were actually revealed to the ancients through the art of alchemy.