Malleus Maleficarum

The Malleus Maleficarum, commonly known as the Hammer of Witches, stands as the most renowned treatise addressing witchcraft. Attributed to the German Catholic figure Heinrich Kramer, also known as Henricus Institor in Latin, it first emerged in the city of Speyer in 1486. Widely regarded as the quintessential compilation of demonological literature from the 15th century, this work reflects Kramer's attributions of his own desires onto women, presenting them as aligned with the stance of the Church. The book faced censure from leading theologians of the Inquisition at the Faculty of Cologne due to its advocacy of unethical and illegal practices and its departure from established Catholic doctrines of demonology.

The Malleus Maleficarum, also known as the "Hammer of Witches," vehemently condemns sorcery as heresy, a grave crime during its era, and urges secular authorities to rigorously prosecute practitioners. The text advocates the use of torture to extract confessions and asserts that death is the sole definitive method to eradicate the perceived malevolence of witchcraft. During its circulation, the prevailing punitive measure for heretics was death by burning at the stake, a fate the Malleus Maleficarum also deemed suitable for "witches." Curiously, despite the Church's disapproval, the Malleus Maleficarum gained substantial traction among the general populace for a period of time.

In 1519, a new author, Jacob Sprenger, was unexpectedly added to the Malleus Maleficarum. This puzzling addition, occurring 33 years after the book's initial printing and 24 years after Sprenger's passing, has left historians contemplating the reasons behind it. Notably, Kramer, the primary author, penned this pivotal work after being banished from Innsbruck by the local bishop due to allegations of misconduct. The tribunal was halted due to Kramer's fixation on the sexual conduct of the accused, Helena Scheuberin, diverging from the papal bull's original intent, which focused on heresy rather than sexual impropriety.

The book was later revived by royal courts during the Renaissance, and contributed to the increasingly brutal prosecution of witchcraft during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Witchcraft had long been forbidden by the Church, a stance that was elucidated in the Canon Episcopi written in about AD 900. This document asserted that witchcraft and magic were mere delusions, and that those who held beliefs in such matters "had been seduced by the Devil in dreams and visions". Despite this, supernatural intervention was considered plausible during this era, as evidenced by the use of ordeals, which were later incorporated into the proceedings of witch trials. It is an established belief within doctrine that demons can be expelled through the use of specific sacramental exorcisms. The Malleus, for instance, identifies exorcism as one of the five methods to counter the assaults of incubi. Typically, prayer and transubstantiation are not considered to fall under the classification of magical rites.

In 1484, clergyman Heinrich Kramer embarked on one of his first attempts at prosecuting alleged witches in the Tyrol region. Unfortunately, his efforts ended in failure, as he was expelled from the city of Innsbruck and dismissed by the local bishop who deemed him "senile and crazy." Scholars like Diarmaid MacCulloch suggest that Kramer's writing of the book was driven by a need for self-justification and revenge. Ankarloo and Clark further argue that Kramer aimed to expound his own beliefs on witchcraft, systematically refute claims denying its existence, discredit skeptics, assert that witchcraft was predominantly practiced by women, and persuade magistrates to adopt his recommended procedures for identifying and convicting witches.

Some academic researchers have put forward the idea that, subsequent to unsuccessful initiatives in Tyrol, Kramer sought explicit authorization from the Pope to pursue allegations of witchcraft. In 1484, Kramer obtained a papal bull known as Summis desiderantes affectibus, which granted comprehensive papal endorsement for the Inquisition to address what was categorised as acts of witchcraft in a broad sense. Moreover, it conferred specific permissions to Kramer and Dominican Friar Jacob Sprenger. However, other experts have contested the notion that Sprenger collaborated with Kramer, contending that the evidence indicates Sprenger actually adamantly opposed Kramer. This opposition extended to banning Kramer from Dominican convents under Sprenger's jurisdiction and prohibiting him from preaching.

In the words of Wolfgang Behringer:

Sprenger had tried to suppress Kramer's activities in every possible way. He forbade the convents of his province to host him, he forbade Kramer to preach, and even tried to interfere directly in the affairs of Kramer's Séléstat convent... The same day Sprenger became successor to Jacob Strubach as provincial superior (October 19, 1487), he obtained permission from his general, Joaquino Turriani, to lash out against Master Heinrich Kramer, inquisitor.

The preface of the Malleus Maleficarum also contains a purported unanimous endorsement from the University of Cologne's Faculty of Theology. However, numerous historians have contended that evidence from sources other than the Malleus confirms that the university's theology faculty actually censured the book for employing unethical methods and for diverging from Catholic theology on several significant matters. Some have even suggested that Institoris fabricated a document to falsely assert their supposed unanimous approval.

The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which "denied any authority to the Malleus" in the words of historian Wolfgang Behringer.

Before the 15th century, it was uncommon for individuals to face prosecution for witchcraft. However, the growing prevalence of heresy prosecutions and the inability to fully eradicate heretical beliefs set the stage for the subsequent criminalization of witchcraft. As belief in witches became widely entrenched in European society by the 15th century, those convicted of witchcraft had typically faced penalties such as public penances, such as a day in the stocks. The situation changed drastically with the dissemination of the Malleus Maleficarum, which led to a widespread acceptance of witchcraft as a genuine and perilous phenomenon. The period between 1560 and 1630 witnessed the most severe witchcraft prosecutions, which began to wane in Europe around 1780.

Particularly in the 16th and 17th centuries, an intense and widespread debate on the nature of witches captured the attention of demonologists across Europe. This period saw the publication of numerous printed sermons, books, and tracts as demonologists sought to grapple with and define the essence of witchcraft. Notably, the Catholic Church emerged as a significant influencer in shaping the discourse on demonology during this time. Despite the tide of the Reformation, the debate on witchcraft remained largely unaffected, with even Martin Luther himself being convinced of the reality and malevolence of witches. Luther's beliefs further contributed to the evolution of Protestant demonology, underscoring the enduring significance of this heated discussion during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Malleus Maleficarum consists of the following parts:

Justification (introduction, Latin Apologia auctoris)

Papal bull

Approbation by professors of theology at University of Cologne

Table of contents

Main text in three sections

Justification (Apologia auctoris)

In this part it is briefly explained that prevalence of sorcery which is a method of Satan's final assault motivated authors to write the Malleus Maleficarum:

[...] [ Lucifer ] attacks through these heresies at that time in particular, when the evening of the world declines towards its setting and the evil of men swells up, since he knows in great anger, as John bears witness in the Book of Apocalypse [12:12], that he has little time remaining. Hence, he has also caused a certain unusual heretical perversity to grow up in the land of the Lord – a Heresy, I say, of Sorceresses, since it is to be designated by the particular sex over which he is known to have power. [...] In the midst of these evils, we Inquisitors, Jacobus Sprenger together with the very dear associate [Institoris] delegated by the Apostolic See for the extermination of so destructive a heresy [...] we will bring everything to the desired conclusion. [...] naming the treatise the "Hammer for Sorceresses," we are undertaking the task of compiling the work for an associate [presumably, an ecclesiastic] [...]

Papal bull

Copies of the Malleus Maleficarum include a reproduction of a papal bull known as Summis desiderantes affectibus that is addressed to Heinrich Institoris and Jakob Sprenger. In this document, Pope Innocent VIII acknowledges the reality and harmful impact of sorceresses through their involvement in the acts of Satan.

According to the date on the document, the papal bull had been issued in 1484, two years before the Malleus Maleficarum was finished. Therefore, it is not an endorsement of a specific final text of the Malleus. Instead, its inclusion implicitly legitimizes the handbook by providing general confirmation of the reality of witchcraft and full authority to Sprenger and Institoris in their preachings and proceedings:

And they shall also have full and entire liberty to propound and preach to the faithful Word of God, as often as it shall seem to them fitting and proper, in each and all of the parish churches in the said provinces, and to do all things necessary and suitable under the aforesaid circumstances, and likewise freely and fully to carry them out.

— Summis desiderantes affectibus

Approbation

This part of the Malleus is titled "The Approbation of The Following Treatise and The Signatures Thereunto of The Doctors of The Illustrious University of Cologne Follows in The Form of A Public Document" and contains unanimous approval of the Malleus Maleficarum by all the Doctors of the Theological Faculty of the University of Cologne signed by them personally. The proceedings are attested by notary public Arnold Kolich of Euskirchen, a sworn cleric of Cologne with inclusion of confirmatory testimony by present witnesses Johannes Vorda of Mecheln a sworn beadle, Nicholas Cuper de Venrath the sworn notary of Curia of Cologne and Christian Wintzen of Euskirchen a cleric of the Diocese of Cologne.

Text of approbation mentions that during proceedings Institoris had a letter from Maximilian, the newly crowned King of the Romans and son of Emperor Frederick III, which is summarized in the approbation: "[... Maximilian I] takes these Inquisitors under his complete protection, ordering and commanding each and every subject of the Roman Empire to render all favor and assistance to these Inquisitors and otherwise to act in the manner that is more fully contained and included in the letter." Apparently, in early December 1486, Kramer actually went to Brussels, the Burgundian capital, hoping to obtain a privilege from the future Emperor (Kramer did not dare to involve Frederick III, whom he had offended previously), but the answer must have been so unfavorable that it could not be inserted into the foreword.

Main Text

The Malleus Maleficarum, a notorious medieval text, sets forth the belief that witchcraft requires three essential components: the malevolent intent of the witch, the assistance of the Devil, and the acquiescence of God. This influential treatise is structured into three distinct sections, with the initial part targeting clergy members and endeavoring to counter arguments from skeptics who cast doubt on the existence of witchcraft, thus impeding its persecution.

The second section provides a detailed explanation of the various manifestations of witchcraft and presents potential remedies. In the third section, the aim is to support judges in addressing and countering witchcraft, as well as to relieve inquisitors of some of their responsibilities. Throughout all three sections, the dominant themes revolve around defining witchcraft and identifying those who practice it.

Section I

Section I delves into the theoretical examination of witchcraft, exploring it from the perspectives of natural philosophy and theology. It seeks to determine the reality or mere illusion of witchcraft, pondering if it is the deceptive apparitions of the devil or the product of frenzied human imagination. Ultimately, it asserts the authenticity of witchcraft by reasoning that its existence is intertwined with the very real presence of the Devil. This is illuminated by the notion that witches forged a pact with Satan, granting them the ability to orchestrate malevolent sorcery, thereby cementing the profound connection between witches and the Devil.

Section II

The text delves into the discussion of matters of practice and actual cases, shedding light on the powers of witches and their recruitment strategies. It posits that it is predominantly witches, rather than the Devil, who undertake recruitment activities, often by engineering misfortunes in the lives of upstanding matrons that lead them to seek the aid of a witch. Additionally, it explores the introduction of young maidens to seductive young devils. Furthermore, it provides insights into the casting of spells by witches and outlines remedies that can be implemented to thwart witchcraft or aid those who have fallen victim to it.

Section III

Section III of the Malleus Maleficarum serves as the legal segment, outlining the procedure for prosecuting individuals suspected of witchcraft. Specifically designed to guide lay magistrates through the process, this section meticulously details the steps involved in conducting a witch trial. It addresses the initiation of the proceedings, the collection of accusations, the interrogation of witnesses (often involving torture), and the formal charging of the accused. Notably, the text includes the stark assertion that women who did not exhibit distress during their trials were immediately deemed guilty of witchcraft.

The first section of the book's main text employs the scholastic methodology of Thomas Aquinas, known for his mode of disputed questions in the Summa Theologica. This method, a standard in scholastic discourse with a long tradition, is prevalent throughout the Malleus, drawing primarily from Aquinas's works. His influence extends across all sections. In Section II, Formicarius by Johannes Nider serves as a significant source, while Section III heavily relies on Directorium Inquisitorum by Spanish inquisitor Nicholas Eymeric.

The Malleus Maleficarum, a infamous manual for witch hunters, advocated not only the use of physical torture, but also the use of deceptive tactics to extract confessions from their victims. The book describes a method where the judge, along with other devout individuals, would try to persuade the accused to confess willingly. If the accused refused, the attendants would then proceed to fasten the victim to an instrument of torture, all the while pretending to be distressed. Afterward, at the request of some present, the prisoner would be released and taken aside for further persuasion, leading the accused to believe that confession would spare them from death.

All confessions acquired with the use of torture had to be confirmed: "And note that, if he confesses under the torture, he must afterward be conducted to another place, that he may confirm it and certify that it was not due alone to the force of the torture."

However, if there was no confirmation, torture could not be repeated, but it was allowed to continue at a specified day. The guideline stated, "But, if the prisoner will not confess the truth satisfactorily, other sorts of tortures must be placed before him, with the statement that unless he will confess the truth, he must endure these also. But, if not even thus he can be brought into terror and to the truth, then the next day or the next but one is to be set for a continuation of the tortures – not a repetition, for it must not be repeated unless new evidences produced. The judge must then address to the prisoners the following sentence: We, the judge, etc., do assign to you, such and such a day for the continuation of the tortures, that from your own mouth the truth may be heard, and that the whole may be recorded by the notary."

This point in history marks a significant shift in the perception of witchcraft, where it transformed into an independent antireligion. The once powerful position of the witch in relation to deities was replaced by complete subordination to the devil, diminishing her ability to compel deities to heed her desires. As a result, the witch was construed as a puppet of Satan, embodying the concept of "Satanism" or "diabolism" in the realm of magic. According to this perspective, witches were viewed as members of a malevolent society overseen by Satan, devoted to perpetrating harmful acts of sorcery (maleficia) on others.

It is worth noting that not all demons do such things. The book claims that "the nobility of their nature causes certain demons to balk at committing certain actions and filthy deeds." Though the work never gives a list of names or types of demons, like some demonological texts or spellbooks of the era, such as the Liber Juratus, it does indicate different types of demons. For example, it devotes large sections to incubi and succubi and questions regarding their roles in pregnancies, the submission of witches to incubi, and protections against them. The text provides insightful perspectives on the diverse nature of demons and their specific attributes, shedding light on the complexities of their existence and behavior.

In 1484, Heinrich Kramer made one of the earliest attempts at prosecuting alleged witches in the Tyrol region, which proved unsuccessful, leading to his expulsion from the city of Innsbruck. Scholar Diarmaid MacCulloch suggests that Kramer's writing of the book served as a form of self-justification and revenge. Additionally, Ankarloo and Clark argue that Kramer aimed to articulate his own perspectives on witchcraft, systematically counter arguments denying its existence, undermine skeptics, and promote the idea that witches were predominantly women. His ultimate goal was to persuade magistrates to adopt his recommended procedures for identifying and convicting witches.

The sex-specific theory developed in the Malleus Maleficarum played a crucial role in establishing a widely accepted belief in early modern Germany that witches were predominantly women. While subsequent works on witchcraft have diverged from the Malleus, there remains an overarching consensus that women are more likely to be witches than men. This widespread acceptance meant that only a minority of authors felt compelled to justify the association between women and witchcraft. For those who did, explanations ranged from attributing female witchery to perceived physical and mental fragility (a traditional medieval belief) to linking it with female sexuality.

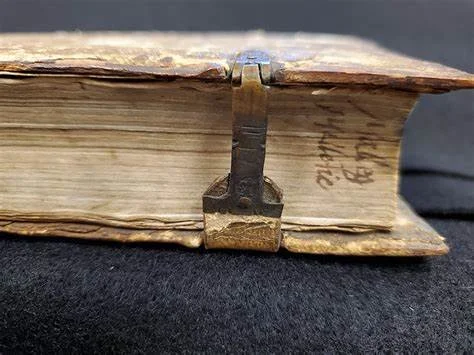

Between 1487 and 1520, the Malleus Maleficarum saw twenty editions, and another sixteen were published from 1574 to 1669. The rapid spread of this infamous work across Europe during the late 15th and early 16th centuries was made possible by the revolutionary advent of the printing press, introduced by Johannes Gutenberg around the mid-15th century. The emergence of printing, just three decades before the first release of the Malleus Maleficarum, fueled the fervent pursuit of witch hunts. As Russell noted, "the swift propagation of the witch hysteria by the press was the first evidence that Gutenberg had not liberated man from original sin."

The late 15th century was a time of significant religious unrest and conflict. The rise of the Malleus Maleficarum and the resulting witch craze capitalized on the growing intolerance brought on by the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Europe. As the Protestant and Catholic factions fiercely vied to uphold their respective interpretations of faith, a climate of zealotry and contention enveloped the continent. Ultimately, the Catholic Counter-Reformation would quell this religious turbulence, but not before prolonged struggles between the two camps for what each believed to be true and just.